- Home

- About

- Books

- Lac Des Pleurs 2015

- Bicycle Diaries 2011

- Report from Pool Four 2010

- Plunging 2009

- Sylvæ 2007

- Mayflies of the Driftless Region 2005

- The Intruder 2004

- New York Revisited 2002

- The Coriolis Effect 2002

- Ernest Morgan: Printer of Principle 2001

- Emerson G. Wulling: Printer for Pleasure 2000

- I Will Eat a Piece of the Roof, And You Can Eat the Window 1999

- Waterfalls of the Mississippi 1998

- Bad Beat 1998

- A House in the Country 1995

- Wrenching Times 1991

- Farmers 1989

- High Bridge 1987

- Broadsides

- Contact

Sylvæ In Progress Updates March 2006 - March 2008

Stalking down a sugar maple (Acer saccharum) to be felled and sawn into boards and blocks for engraving and printing

March 17, 2006

Over the next year and a half the focus here at Midnight Paper Sales will take a slight shift. Remaining within the vein of natural history, the attention will turn from the banks of the Mississippi and Mayflies of a Driftless Region to the bluffs and forests just above that same river.

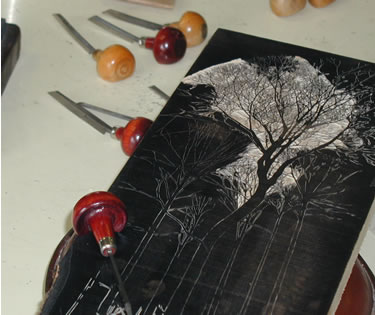

A few of the unfinished engraving rounds.

The woods have been waking up here in Wisconsin. This past month has seen a warm spell that brought on short-sleeves and the bud break. The foliage that is beginning to peak out has made identification a little easier. To date we've catalogued 18 species. Eventually we would like to use the microscopic identification of wood as a further means of classifying a tree. For the time being, though, here is our list:

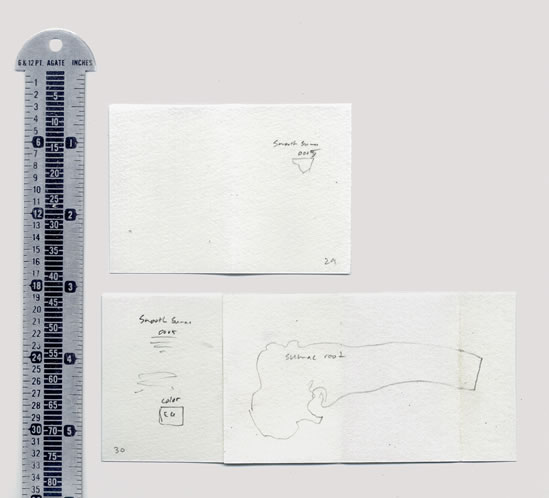

A few of the samples we've gotten so far. From left to right: Ironwood (Ostrya virginiana), Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra), and a Paper Birch root (Betula papyrifera).

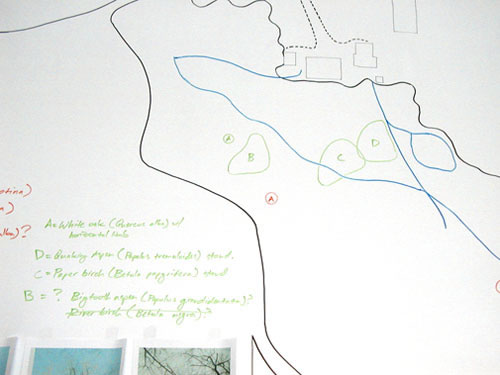

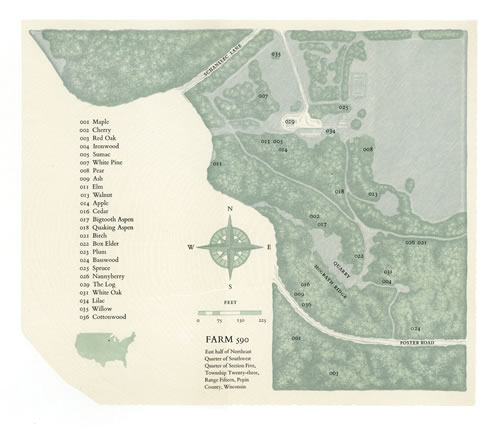

Here at the studio we've installed a large map of the property as. It serves to locate trees that have been cut, stands of interest, and anything else that catches our eye. The hope is to somehow translate it into print within the book, though exactly how is still unclear. I've also been out talking with a few of the old-timers from this area, to hear a first hand account of the recent history of this property.

All in all it's been a busy month here at Midnight Paper Sales. Though there is much work to be done, things are slowly beginning to come together. It's very exciting.

May 30, 2006

May was a busy month with an overhaul of the website, and plenty of printing to be done. Still, there was time to toy around in the studio. Among other things we've been working on bettering our ability to make blocks from the large hard maple half-rounds we cut down this past winter. Below are three stages on the way to a smooth block, that will be ready for engraving.

A maple round, after going through a drum sander. Notice the streaking lines, left by the machine.

The same bock, after some hand sanding. In the upper right corner a circular scratch is visible.

Here is the block after more careful and fine hand sanding, along with a little more ink.

The leaves and flowers of a Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) before pressing

As always there has been time to walk around out of doors, and see what the woods are up to. The sumac have begun to show some color on their fruit and the undergrowth is thick from a recent rain.

Playing around with text, composition, and a long grain foldout.

The fruit of a Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra) on its way to a deep red.

August 11, 2006

After proofing we've decided that the best way (so far) to make blocks from either large rounds or plank side specimens is to back them with a rigid piece of plywood. This makes for a sturdier block in the press, which is less likely to move or buckle before and during printing. For me, seeing the rounds after lamination and sanding has been an exciting step. They have turned from specimen to block. Where once was only imagined potential there is now tangible material that can be printed and played with. The design is coming along as well. A first full-length dummy is in the works and will be done soon. The dummy is a mock version of the book. It will allow us to flip through pages and get a better sense of pacing, typography, and how and where to make changes.

Some of the blocks backed with plywood or particle board.

Cutting the key block for an engraving of the Sugar Maple, from which this actual block was made.

September 18, 2006

A rough dummy has been completed to size. After doing so I felt like the process perhaps had to go back to pagination (a method of organizing thumb-nail sketches of page layouts, much like story boarding) in order to get a better sense of pacing. Pagination allows for a bird's eye view of the book. This is when you are the master of your own universe, and are able to shift pages with ease. It is a bit like shuffling continents on the globe.

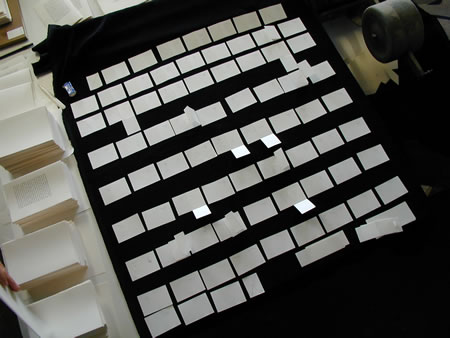

The whole book laid out in pagination (left). Above are two thumbnail layouts for Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra) and its accompanying foldout.

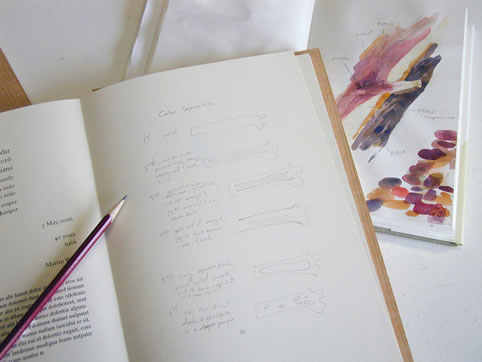

A page from the dummy with notes on color separation along with a color study for Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana).

We have also begun to figure out which species we might like to replicate the wood color for. There have been some color studies as well as notes on how exactly to break down a block through reduction cuts to most faithfully reproduce the color of different parts of the specimen (i.e. sap wood, heartwood, and bark). A reduction cut is simply a multicolored print from the same block. With each new color there is more cut away from the block until you are left with just highlights to be printed. This means you can never reprint the former color again because you have cut away some of its information. The challenge will be to nail the colors as best we can by layering them on top of each other.

October 31, 2006

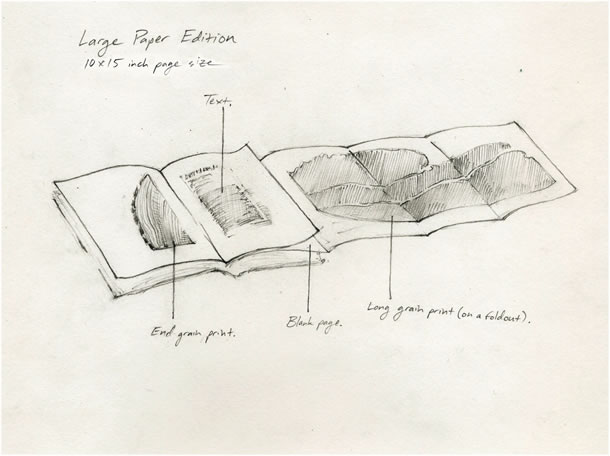

As you may have read above we're beginning to think of the Sylva in terms of three editions. The first edition will have approximately 100 copies, and the images will likely be printed on the same paper as the text. The second edition will most likely have 50 copies. We're thinking of using multiple papers for this edition, which would mean printing the images on a finer hand made paper. The binding would incorporate wooden boards cut from this property. As for the third edition we have not determined the number of copies but it could be as many as 26 or as few as 10. It would be a "Large Paper" edition and very different than the former two. Not only would the size be much bigger, but the binding, paper (entirely hand made), even aspects of the text and typography would differ from the previous two.We've also been mulling over different ways to present the information. One layout would bring the book to a good 200 pages, which is both exciting and daunting. Soon we'll also order the text paper for the first two editions. Within a week we hope to have a life-size dummy using a few different papers to give us an idea of the heft and feel of the actual book.

One of many sketches made while working on layout.

November 6, 2006

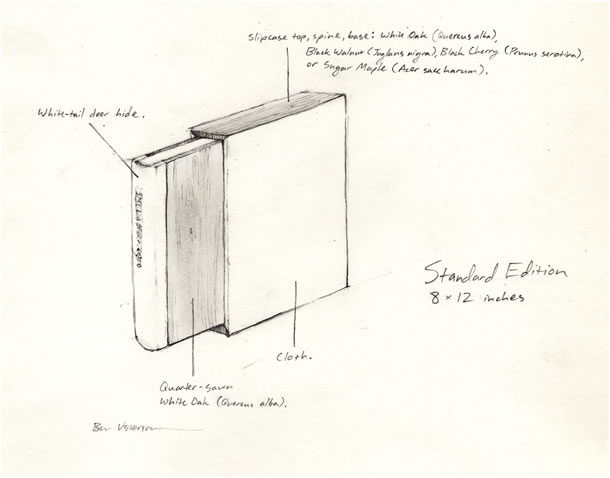

We are now fairly certain the Sylva: Farm 590 will be available in two editions as described below. The prices have yet to be determined.November 22, 2006

It has been quite a couple of weeks. Though there is polishing yet to be done, a lot of the structure of the book has been knocked out. We have not made any final decisions on paper, but we are close. A majority of the specimen blocks have been selected. Fairly soon we'll start to back them with 3/4 inch wood composite countertop material from Great River Industries in Wabasha, Minnesota. After laminating, the blocks will go through the milling process to get them to type high. Then it is on to printing. Some of the blocks will be monochromatic and others will be multi chromatic. For the multi-colored blocks we'll be using the reduction cutting method. Some specimens will have as few as two press runs or as many as six, with the overall goal of reproducing as faithfully as we can the actual colors and textures found in the wood itself.

A Sweet Apple specimen (Malus pumila) with its corresponding proof.

December 12, 2006

After another round of proofing we're almost certain of our paper choices. It seems the standard edition is to be printed entirely on Zerkall Book Laid. The text for the Large Paper edition is to be printed on Velke Losiny. The images for the Large Paper edition, after this last round of proofing, will likely be printed on a special making of Zerkall no. 7625. This paper is calendared to the maximum the mill is capable of. This means it is the smoothest paper the manufacturer is able to make. It was first created for Edwina Ellis, a British wood engraver, and is sometimes referred to as the Edwina Ellis making of Zerkall no. 7625. The smooth surface shows an incredible amount of detail, yet the paper still accepts ink gracefully. The feel and weight of this sheet pairs well with the Velke Losiny, and has precise, supple folds.

Some of the most recent proofs, including those on the Zerkall no. 7625. The specimen represented here is White Oak (Quercus alba).

The discussion continues for binding methods. Craig Jensen of BookLab II is now consulting with Gary Frost, conservator at the University of Iowa. There is a correction to make. In the last in progress entry of 22 November, 2006 I called the Large Paper binding method, "medieval wooden board binding." The correct term is laced board binding sewn on cords.

February 7, 2007

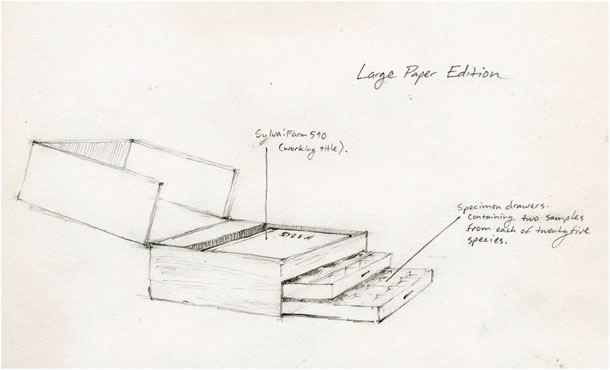

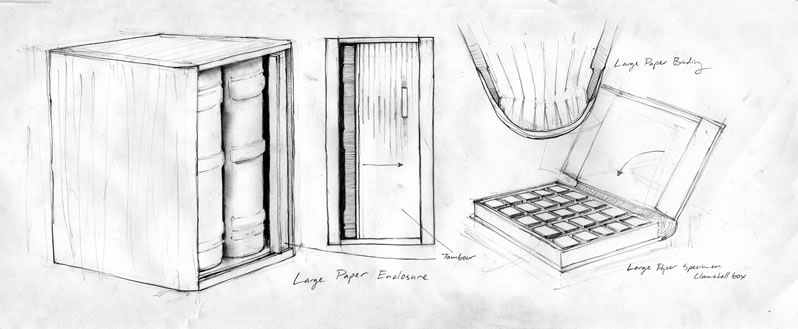

My apologies for the belatedness of this update. It has been a very busy time here at Midnight Paper Sales. The Sylva has continued to evolve. The enclosures/slipcases of both editions are taking shape. As mentioned before we will be working with Craig Jensen of BookLab II on the binding. We have also partnered up with Dick Sorenson, a fine woodworker in the twin cities, who will be helping us with the enclosures.The Standard edition will now come with a wooden slipcase, built using materials taken from this property, and will most likely incorporate dove-tail joinery. The Large Paper edition enclosure has changed as well. Instead of a clamshell box with drawers of specimens (see November 22, 2006 in progress entry) it will be large wooden slipcase with a tambour on the spine edge. A tambour opens by sliding out of the way, and into a hidden compartment, like a roll top desk. When opened, this particular tambour will reveal the book and an accompanying clamshell box of specimens. This specimen box will replace the earlier drawer concept.

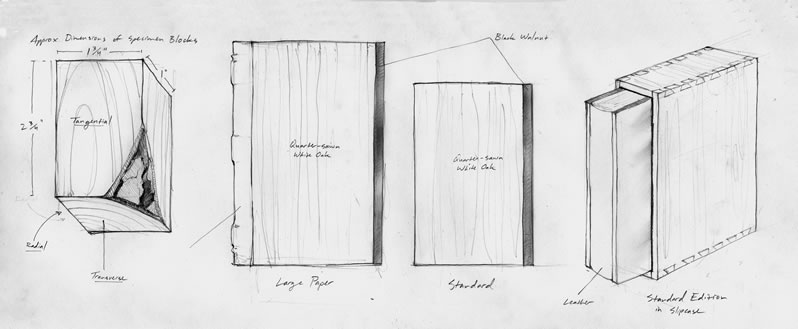

The problem had been how to take the specimens from a vertical standing position on a bookshelf to a horizontal viewing position on a table. We felt the single clamshell box solved this problem and made a more elegant companion to the book than the two drawers. Additionally the specimens will no longer number 50 (one long grain and one end grain for each of 25 species). Instead there will be 25 larger blocks (one of each species) taken from the property. This change resulted from the need to show three views of each species' grain (tangential, radial and transverse). These three views are important in identifying a species of wood, and we felt they must be presented. It will involve careful planning and cutting, but will be worth it. Below are some recent sketches of the enclosures for both editions.

From left: Large Paper enclosure, Large Paper frontal view, Large Paper binding detail, clamshell box containing specimens.

From left: Sketch of specimen block, Large Paper editions, Standard edition, Standard edition w/dovetailed slipcase.

In addition to the structure of the book, the recent focus has also been on the images and engravings. We have completed a round of proofs of a block of Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana). This served as an experiment for how we will approach many of the multi-chromatic images in the book. There are five stages of this proof. They are printed from two blocks, using the reduction cutting method. One block was the actual specimen, which thankfully held up well over the course of printing. The second block was cut from Hard Maple (Acer saccharum). The first stage was printed directly from the Cedar in a light sapwood color. This meant printing the annual growth rings (especially the darker ones) on several layers of ink. In the future we are considering printing the engraved annual lines first so as to preserve their clarity.

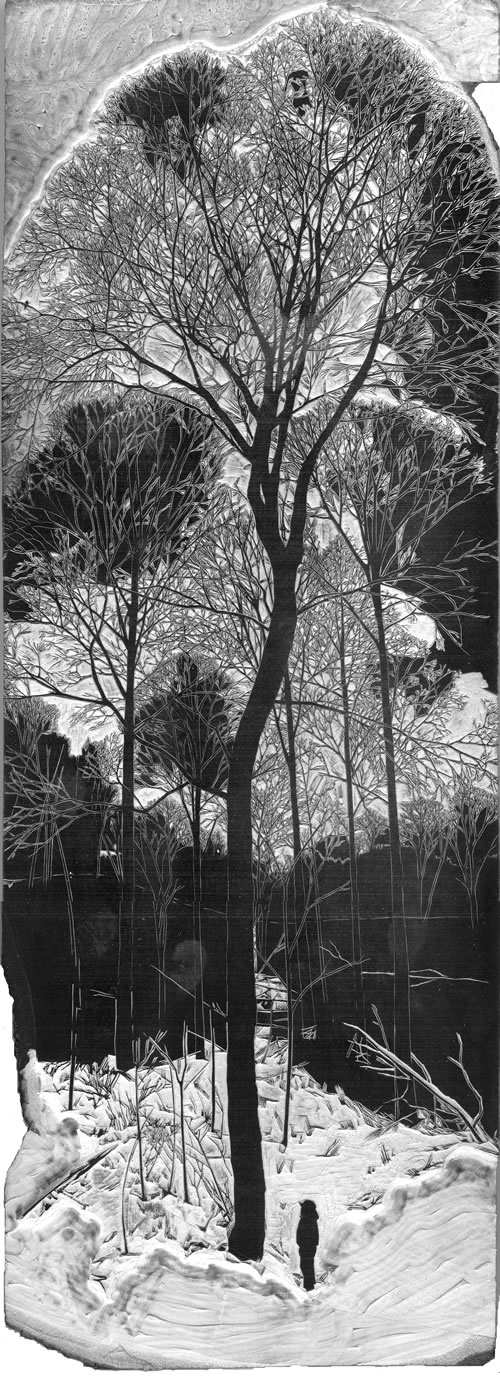

The portrait of the Hard Maple (Acer saccharum) is still in progress, but coming along nicely.

Stage 1: Printed directly from Cedar specimen.

Stage 2: Printed from specimen after engraving annual growth lines and bark.

Stage 3: Printed from specimen after engraving heartwood annual growth lines and bark.

Stage 4: Heartwood and bark detail printed from separate maple block.

Stage 5: Heartwood annual line detail and further bark detail printed from maple block.

The portrait of the Hard Maple (Acer saccharum) in progress.

March 6, 2007

Standard Edition dummy with three page foldout.

Trial board of White Oak (Quercus alba) for Large Paper edition.

The entire text will be sent out for editing today. It covers, among other things, how Pear wood engraves, White Ash's role in the Pepin v. Stockholm baseball rivalry, the politics of Aspen and Sugar Maple, and the milling of Red Oak. We have a sample board from BookLab II as well as a dummy for the Standard Edition (both shown above). Though these are not the final materials, they have given us a good idea of the aesthetic and heft of both books. A majority of the paper will also arrive late this week, via a long journey across the Atlantic. Next week we'll be cutting and sorting. Within 14 days we ought to start printing the images. .

March 27, 2007

Printing has begun! There are many days ahead, each with some new battle, some unforeseen problem to be tackled. That said, it is off to a promising start and we look forward to the weeks and months ahead with steady determination. There is a sense of flexibility that we have begun to adopt in regards to the images we are printing. Taking impressions directly from so many varied species of wood is uncharted territory. In the runs completed thus far it seems there are times when only a kiss of ink is required on a delicate block. Others call for a strong impression to pull out the details. The ability to adjust a printing plan in the face of such needs is essential.

It will take us considerable time to develop a regular set of printing methods, catered to this project. One shift we have had to make is in how we approach the end grain specimens versus the long grain specimens. They each have distinct characteristics. The end grain specimens allow for much more detailed cutting than their long grain counterparts. They also tend to be smaller. When second or third blocks are required we can easily mill them out of hard maple. With long grain pieces we have to rely more on reduction cutting. This, coupled with the less accurate nature of wood cut (vs. engraving), has led us to manipulate these images more through color and careful printing. This is not to say these are not essential to all prints in the book (including the end grain specimens). I only mean that we have one less tool with the long grain. When possible we will let these specimens speak for themselves. There will be instances where the long grain prints have an incredible amount of detail, but it will not come from cutting or engraving. Instead it will be the knots and grain of a specimen, coaxed out with deliberate inking and impression.

Working on image placement.

Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra) long grain.

Consulting the printing schedule.

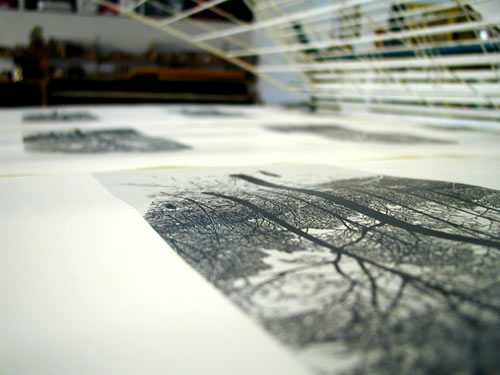

The Basswood (Tillia americana) long grain prints drying.

May 7, 2007

Wild Plum (Prunus americana) on the press.

Wild Plum (Prunus americana) on the drying rack.

Printing is well under way now. There is a rhythm in the studio, and we have developed a fairly solid method for dealing with each new image. The color choices that need to be made are becoming easier, as are the cutting plans which break each image into several states. Though there is much less uncertainty than at the onset there are still plenty of opportunities for vivid and aesthetically pleasing surprises. A few days ago, during the printing of wild plum (Prunus americana) we were a little nervous about our color choices and wood cuts. The wood of wild plum is far darker than most of the species we had printed to date, and the marks of a wood cut can be much bolder than those of an engraving. Anxiety gave way to satisfaction when we saw that all of our planning was working out for the better.

There are still block making issues that arise from time to time as well. Below is an example of the latest method of lock up. Instead of backing this hard maple block (Acer saccharum)with composite board it has been affixed with Bondo to a matrix of white oak.

Hard Maple (Acer saccharum) in Bondo.

Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides) and Dean waiting for the Bondo to dry.

June 26, 2007

Working both the Heidelberg and the Vandercook simultaneously. Two presses at once.

A sketch of the layout for the Aspen page.

All of the specimens printed thus far (37 ) hanging on the wall.

The end grain engraving from the old log building on the property.

Today marks press run number 110 of the images. That's about 23,100 revolutions of the press. We're over three-quarters of the way through printing the specimens, and we're starting to feel the toll of the past fourteen weeks. As the end of printing images nears we find ourselves in the midst of the largest specimens in the book - the "three panel bleeds." They're up to 23 by 12 1/2 inches in size, and are by far the most time consuming to prepare, cut and print.It is good we are tackling these images now,rather than earlier, because they require all the tricks we have learned along the way. Still, it is tiring to have the last leg of the climb be the steepest. We're looking forward to printing page numbers of all things.

The first empty kiln

Also, the first batch of wood has come out of the drying kiln. Now they're off to the woodworker for final proto-types of the enclosures. The kiln dries, then dampens, then dries again, resulting in wood that has a consistent moisture level throughout. Too much water and your board will warp and check (crack). This moisture content affects both printmaking and binding. We're working on including the kiln meter readings in an appendix in the back of the book, along with a record of color work for each press run. Not only are these statistics exciting to manipulate typographically, but they serve to further document just how these trees made their way to the printed page.

July 5, 2007

We're nearly done with the images now. It has been a long journey - one that has taken about 20 weeks. Our methods have progressed since first printing that small basswood specimen in mid-March. We've been very conscious about continuity within the book, making sure that we didn't push any single image too far in one direction as to make it stand out too much against the others. Still, there have been opportunities to tinker with our methodology along the way, making subtle adjustments to enrich colors or push contrast, and varying the cutting method to smooth edges or exhibit texture. We'll approach the final specimen to be printed (a cottonwood burl for the frontice piece) with all the experience and cumulative knowledge gained over the past 5 months.

August 9, 2007

A handful of the blocks used in the 51 specimen images.

Ink cans stacked after printing.

IMAGES COMPLETE!

September 17, 2007

The finished map of Farm 590 complete with text.

With the images finished we're on to type. It is amazing how the addition of even a small piece of text, alongside an engraving, transforms a sheet from raw image to book page.

Drying portrait of Hard Maple from which were milled many of the blocks used in printing.

Aside from the current printing progress there has even been a round of trimming and folding, further changing the context of each sheet and moving it closer towards a finished book. Dick Sorenson, the woodworker, has also built a prototype of the tambour for the large paper enclosure. The action of its opening and closing is incredibly smooth, and he has been able to make the closed face seamless, with each rib flush to the other. He's also milled the first set of cover boards for the standard and is beginning the first specimen tray for the large paper, which will hold one block from each of the twenty-five species.

Dick Sorenson's tambour prototype.

December 1, 2007

It has been three weeks since our trip to Oxford, England for the 2007 biennial Oxford Fine Press Book Fair; three weeks since the Sylvæ won the Gregynog Letterpress Prize there. It has been a full month since finishing printing on the standard edition, a little less than that since holding the first bound copy in our hands (just hours before the plane left for the British Isles). A month ago we were in the final rush of printing, folding and collating that single book, our blinders on, able to see only text, image, layout; able to hear only the heavy rhythm of the Heidelberg, the whisper of new ink on the Vandercook's rollers. Even now, with a little distance and the advantage of hindsight, it is impossible for me to see how we did it. I do not doubt that we accomplished it, but the exact workings of the project, the intricacies involved, and the myriad of decisions made is lost on me. I'm sure the same is true with anything of similar scope.

Despite having worked intimately with this book for the past two years, it is hard to recall anything, save the most basic details. This, I know: the Sylvæ became something much larger than either of us had anticipated. We rose to the task, sometimes out of desire, other times out of need. It taught the both of us, I believe, about projects of this magnitude – how they have a life of their own at times. It opened the woods around us, showing them to be witnesses of human history, and that the whole is made up of many individuals, which, when looked at closely, reveal so many different stories, to say nothing of different printing surfaces and aesthetics. Lastly, it was quite an experience to balance an overall plan with the need to adjust and change when dealing with so many different species, images and blocks.

Perhaps I'm getting carried away. It was not some Herculean feat, though at times it did seem bigger than the both of us. Rather, it was a large project and quite a collaboration, which yielded, among other things, a fine book which I am honored to have worked on.

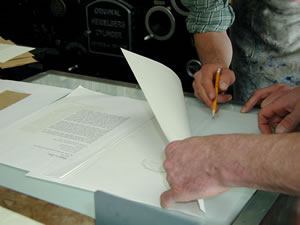

March 8, 2008

Four months have passed since Ben left for Georgia, and I’m still busy finishing up the large paper edition of the Sylvæ.Trimming the text sheets has proved to be challenging, mostly due to the wild nature of hand made paper, and the unevenness of its deckled edges. Emerson Wullling once told me, when asked about deckles that he preferred to cut them off. I didn’t understand why at the time, but I do now. The uneven nature of deckles (especially with hand made paper) makes squareness of cut edges, as they relate to deckled edges, difficult to maintain. In the case of the large paper Sylvæ, with fold-out images attached to the trimmed fore edges of hand made sheets,; it is a devilishly difficult problem. If the fore edge of the hand made text sheet isn’t perfectly square to the head of the sheet, the folded image sheet will deflect, and refuse to fold into the text sheet in line with the rest of the book. Each hand made sheet in the large paper Sylvæ must be trimmed by hand on the Jaques board sheer. This involves marking the cuts in pencil on the light table, and then making three separate cuts. This has proved to be a long and tedious process that has literally taken months to do. Also in the works is the machining of the specimen blocks, which I am doing here in the woodshop at Midnight Paper Sales. Dick Sorenson is preparing a first set of boards that will prove the binding of the book. Craig Jenson at Booklab 2 has made up an initial text block, and we will (hopefully) have the first large paper copy ready to be installed in the exhibit space at the Andersen Horticultural Library by the end of the month. 4 of the 26 copies of the large paper Sylvæ remain unspoken for. The price is $7500.Bill and Vicky Stewart (the Vamp and Tramp) are currently on a West Coast swing of visits with librarians, and the resulting orders for the standard edition of Sylvæ have been very encouraging. Bill and Vicky’s love of (and dedication to) the contemporary book arts scene is remarkable, and much appreciated. 29 of the 120 standard Sylvæ remain available.

This project has been, for me, the ultimate collaboration. The energy and intelligence that Ben Verhoeven brought to the process were fantastic.His “in progress” reports added a helpful dimention in making the process more accessible to you. I extend my heart-felt thanks to him, and wish him success in future ventures. Copies of his little book Twenty Rows In (his internship project here which was a key part of the inspiration for our Sylvæ) should soon be available. Contact Ben at benjamin.verhoeven@gmail.com for details.

Gaylord Schanilec, Midnight Paper Sales

Row 49 Column 1

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, ne sea vocent scripta abhorreant, facilisi explicari mel ne, ut quo vide ridens. Mei ex quodsi inciderint, quo ad quas deleniti definitionem, vis no wisi graecis offendit. Ius ut everti detraxit expetenda, meis civibus consectetuer ea usu. Ad qui option facilisis consequuntur, pro omnis aliquip vulputate te. Solum affert expetenda eos te, et vim sale iudico impetus, in appetere postulant ius. Alia nihil utroque ex sit.