In early June I visited the lower part of the lake on a turtle expedition with book dealer Rob Rulon-Miller and wildlife biologist John Moriarty. June is the time of year that turtles lay eggs, and I hoped to find one doing so. As the Army Corps of Engineers dredges the channel of the river, large islands of sand are formed. These islands are thoughtfully sculpted, generally with a small, land-locked pond at one end, and an overflow drain pipe to the river.

In the ponds ecosystems form that are ideal for the observation of creatures like water snakes, frogs, dragon flies, and turtles.

John captured two little turtles from last year’s hatch that I took home for observation:

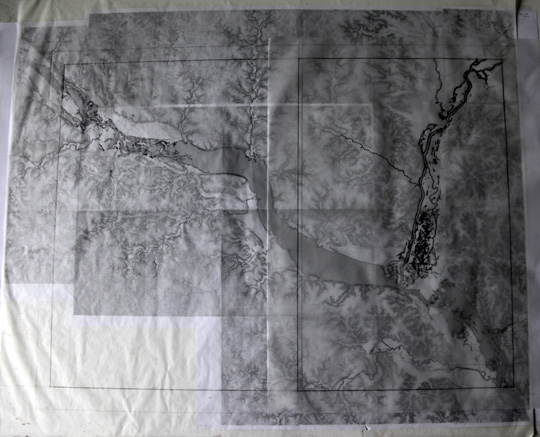

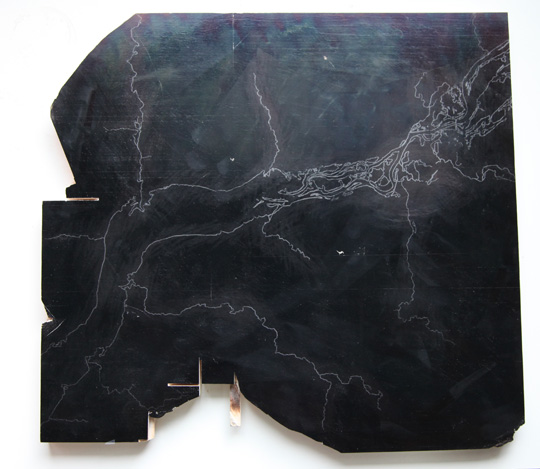

Meanwhile, I’m nearly ready to begin engraving a large foldout map of Lake Pepin. The map will be printed from end grain maple blocks and metal type. Two sections of the map, each the maximum size that my press can print, will be joined, and eventually folded into the book. I’m working from downloaded PDF’s of the latest generation of USGS survey maps. These maps exist in many layers, which can be made visible, or not: I am using only two: hydrology and contours. Overall, my map employs 25 of the USGS maps. They have been scaled to size, printed out, and taped together.

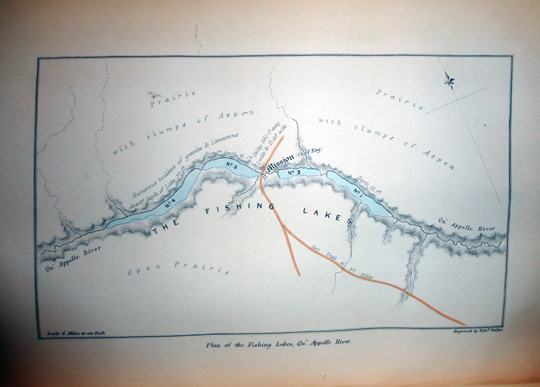

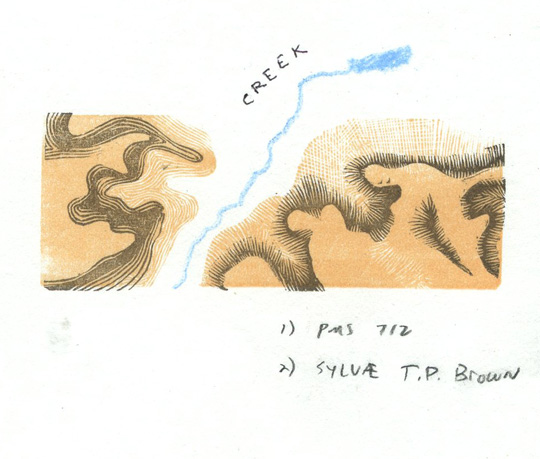

As the text of this volume is historically based (see post of March 19 A Winter That Wasn’t), I have been looking at old maps. To use as a model, I’ve settled on the maps engraved by Edward Weller for Henry Youle Hind’s Narrative of the Canadian Red River… published in 1860, and in particular this little map of “The Fishing Lakes”. I like the typography, the use of color, and the method of showing contour.

I cut a small test block attempting two possible directions I might go in defining contour: modern contour lines, and a stab at hachuring. While using the modern contour lines model would be much easier (and given the massive scale of this map, much less arduous), I’m inclined to go with hachure lines. I obviously have a way to go in developing a satisfactory hachuring technique (engraving in end grain maple offers less precision than engraving in the copper or steel of 19th century map engravers like Weller), but I’m determined to try.

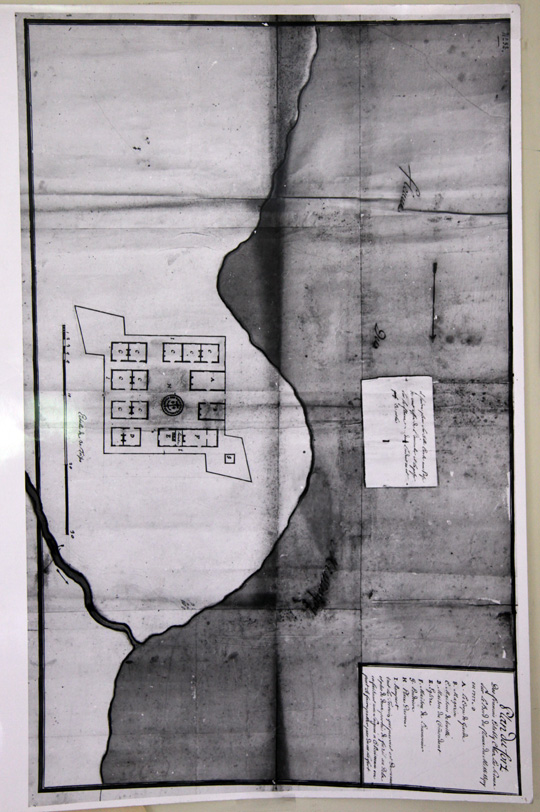

I have a theory that while out on the lake today, if one squints, what one sees isn’t much different from what Hennepin would have seen in 1680. Here is a plan for a French fort on Lake Pepin that was drawn in 1727.

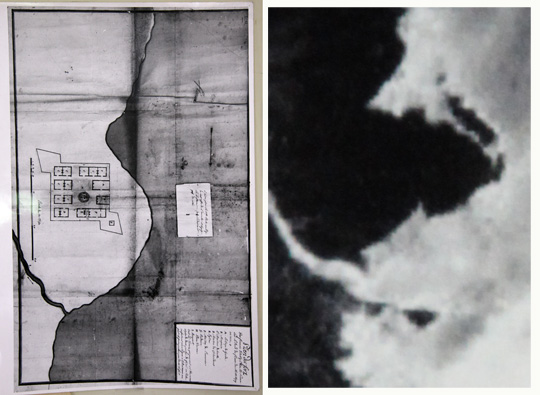

I was thrilled to spot the exact location of the fort by looking at this contemporary USGS photograph.

Though some change has obviously occurred with the shifting of sediment over the years, I think that the basic geography hasn’t.