Dead of Winter • Engraving in the Glow of a Computer Screen

8 January, 2010 • Dead of Winter

I am getting down to the hard business of sifting through specimens, deciding what goes into the first installment of the book, and hammering out rough physical details: page size, paper, contents, cadence, fold-outs, etc.

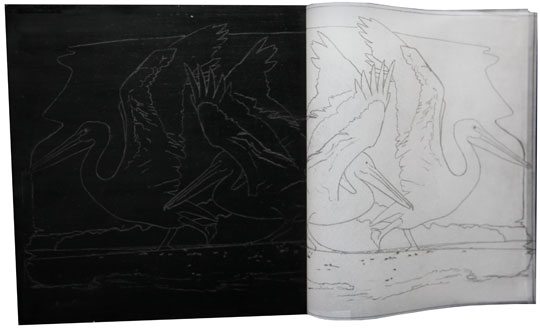

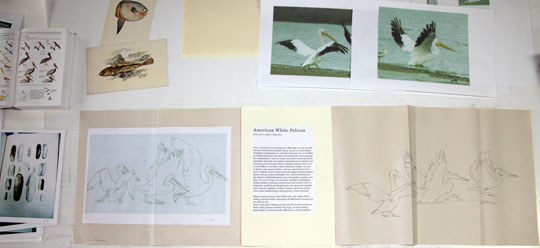

The initial cutting and proofing of the pelican blocks is completed. At least two of them will require reduction cutting while printing: the block is printed in one color, then cut further and printed again, with a second color. This process cannibalizes the block making it impossible to reprint it. I plan to sell prints of some images as I go along, and I’m working out how many sheets will be needed, both for the separate prints and for the book itself. I must make the best possible use of the very expensive vintage English Tovil handmade paper bought for the project last year, and I plan to use at least two other papers in the book: Zerkal 7625, a German mould made paper that I use a lot, and Wookey Hole, a vintage English mould-made. I have decided to print the images on Zerkal, and 1,000 sheets have been ordered. I have 800 sheets of the Tovil, and 500 of the Wookey Hole, on which to print the text.

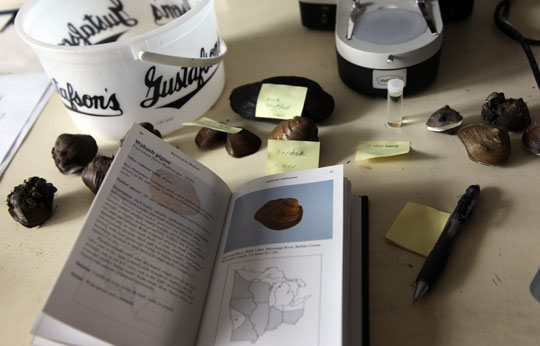

All specimens will be printed actual size. The 6 fish are fairly straight forward, though the Northern Pike will require separate printings and the splicing together of two parts as it’s length exceeds the maximum printing length of the press, about 23 inches. The 45 mussel specimens also present challenges. I am finding, I think, significant variation in individuals within a species, reflecting to some extent changes in the shell as an individual ages. I believe I have representatives of about ten different species, but having gone through the cleaned and recorded specimens, I find 22 individuals of interest for one reason or another. Of course all conclusions that I am making at this point are pretty speculative. I hope to meet an expert soon, possibly Mike Davis of the Minnesota DNR, or Professor Cummings of Illinois, co-author of the field guide which I have been using (Field Guide to Freshwater Mussels of the Midwest, Illinois Natural History Survey, 1992).

16 January, 2010 • Engraving in the Glow of a Computer Screen

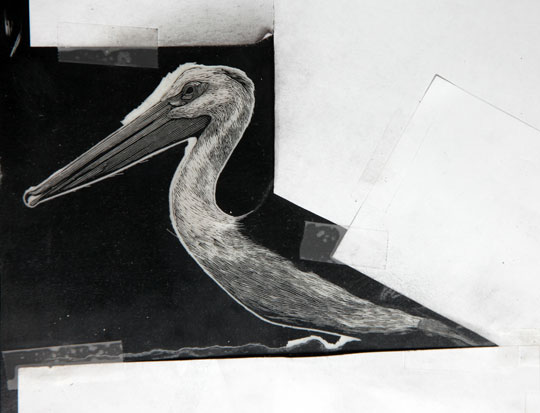

I found the Coreon used for the pelican plates difficult to work with and hard on tools. It does hold a fine line more easily than maple, and has less of a tendency to chip out while clearing than does Resingrave (used for the Ink on the Elbow panorama [click it]). I find working with plastic, however, unpleasant. I have a good supply of end grain maple rounds, and I will go back to wood for the rest of the project. It is a lot of work taking rough sawn half rounds of maple (from the colophon tree in Sylvæ), and making them into smooth and stable type high blocks. The larger the image, the more difficult it becomes to make a flat and stable block, which is essential to fine printing. Given the size of the fish specimens, I am using small strips of wood and glue to join the chunks of maple, a method of joinery typical of end grain wood engraving blocks from the 19th century.

A central problem in the illustration of mussels is presenting views of both the inside and outside of the shells. I am thinking of backing up the inside and outside views of a shell recto-verso: the inside is viewed on one side of a page, and the page is turned to find the outside of the shell printed directly on the back side of the inside view. This will require twice as many mussel images. It is becoming clear that 3 pelicans, 6 fish, and 12 mussels are plenty to deal with this first year.

Sheepshead (Aplodinotus grunniens), is underway. I am engraving in front of the computer, something I have never done before. The photograph is easily manipulated (zooming in, brightening, flipping the image, etc.). I google the species as I work. I am finding interesting articles in scientific journals, but full articles, it seems, can only be viewed for a price. Fair enough.